The shift from determinism to non-determinism in software development is one of the biggest challenges we are facing as an industry right now.

We’ve all been there: you’re working with an AI agent and you think, “What if I add this to my system prompt?” or “Maybe I should give it access to this new MCP tool?”

You make the change, run it once, and it works. Success! You feel like a genius and share with all your colleagues, your followers, your grandmother and your cat. But then, an hour later, you do it again and it fails miserably on the exact same task. Was the change actually good, or did you just get lucky with the first run? “Maybe I didn’t do it right this time…” — turn it off and on again, then do one more time and it works… or does it?

The fact is that there is not only an inherent randomness in the way that LLMs work, but also there are many confounding factors that might contribute to these outcomes.

Because we lived in the deterministic world for so long (did we?), we software engineers are not mentally prepared to deal with this level of uncertainty. We expect computing to be exact as we are told from the very beginning that it is an exact science.

The vibe vs. the science#

I talk a lot about vibe coding with discipline or, in other words, how adding methodology to vibe coding is fundamental to achieve good quality outcomes. This is not a new problem, we have been dealing with software quality issues for decades, but by lowering the barrier to entry and increasing our speed to produce code has upgraded it to a new order of magnitude.

I always surprise myself when I “discover” that an old methodology designed to help teams of humans produce better outcomes often work very well with AI agents. But, in fact, it shouldn’t surprise no one, after all, humans are also non-deterministic by nature. AI is only amplifying some very well known patterns.

While I managed to come up with a fairly decent workflow based on those principles, I never really achieved the level of confidence to say “this is the RIGHT way of doing this”, and this is often because that occasional failure or regression erodes my confidence — “Is this GEMINI.md really the ultimate prompt for Go developers?” “Did I achieve the best system instructions for this task?” “Are my MCP tools the best APIs I could come up with?” — everyday I am swamped with so many doubts that for most of the content I published in the past year I refrained to be very prescriptive and poised everything as case studies — “I did this”, “that happened”. End of story. In scientific literature, case studies are one of the lowest levels of evidence.

I know this is not the typical argument you are going to see in a technical blog, so I need to take a small detour here and talk about myself in a previous life: before settling on a software engineer career, I went to Medical School (I never graduated, but this is a story for another time). In Medicine and other areas of Biology, people are much more used to experimentation and dealing with biases, noise and randomness, because they need to extract “truths” from systems of unknown origins (basically they are reverse engineering the world, how cool is that?) Presenting data of a study as it is isn’t enough; you need to validate it statistically to ensure you remove any potential contamination. Sample size, alpha, p-values, Student T-Test… I hated these terms when I had to do my tests, but little did I know they would be so useful today.

Of course this is not exclusive to Biology, in engineering we often apply statistical techniques when doing research, but I just feel it is not as widespread in our field as it is in others. When I worked in recommendation systems, for example, A/B testing was a critical part of the job to optimise the machine learning algorithms. UX researchers also use extensive A/B testing to determine which interfaces are better than others, and so on.

I wanted to find a way on how to remove the guesswork from my coding agents experimentation, so I realised the best thing I could do is to create an experimentation framework to collect data and do the statistical analysis, thus allowing me to move beyond “I think this works” to “I know this works (with 95% confidence).”

Introducing Tenkai: The agent experimentation framework#

To solve this, I built Tenkai (Japanese for “deployment” or “expansion”, a small Easter Egg for anime lovers). It’s a Go-based framework designed to evaluate and test different configurations of coding agents with statistical rigor.

Think of it as a laboratory for your AI agents. Instead of running a prompt once and hoping for the best, Tenkai allows you to run experiments that will repeat the same tasks over and over (up to an N number of repetitions — your sample size) and it will compare alternatives (different sets of configurations) with each other using statistical tests.

Let’s say Alternative A is your default setup (the experiment “control”) and Alternative B is a new system prompt you want to try. The experiment will run both N amount of times and output a report saying if B is significantly faster, more efficient, or more precise. If the difference is due to coincidence or noise, the framework won’t flag it as significant and you can safely ignore the results.

How it works#

The workflow in Tenkai:

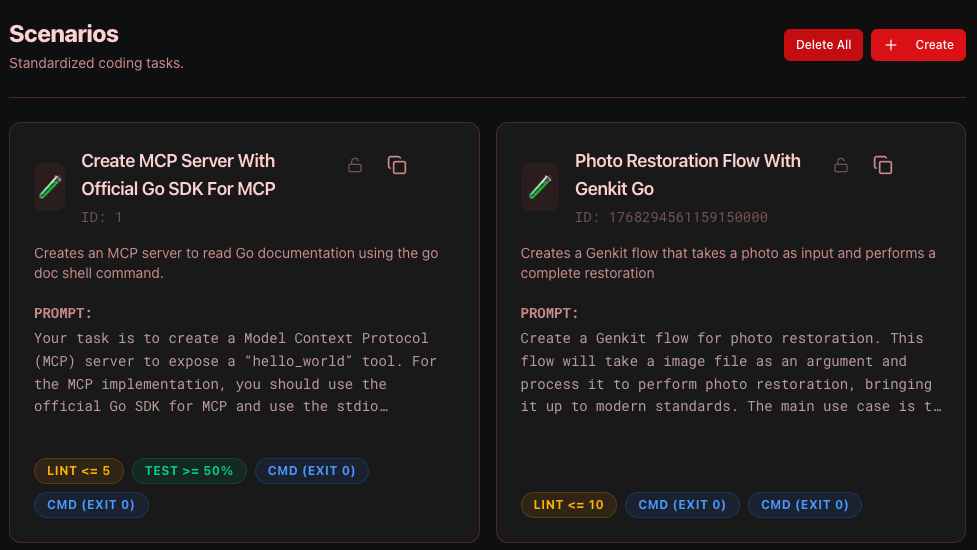

- Define scenarios: A scenario is a standardised coding task (e.g., “Fix a bug in this Go package,” or “Implement a new React component”). It includes validation rules like “Does it compile?” or “Do the tests pass?” For a scenario to be counted as successful it needs to pass all validation criteria you specify.

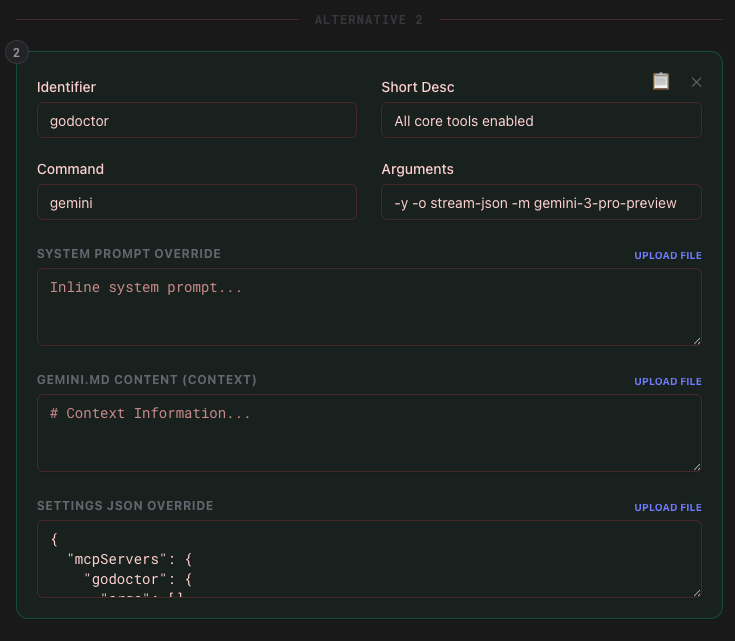

- Create a template: You define what you want to test. For example, your “Alternative A” (control) might be the Gemini 2.5 Flash model, and your “Alternative B” might be Gemini 2.5 Flash with an MCP server configured. You can have up to 10 alternatives in the same experiment template (they will all be compared to control).

- Run the experiment: Tenkai executes each scenario multiple times for each alternative. It isolates the runs in temporary workspaces, manages timeouts, and captures every single event — from tool calls to shell outputs. You can also specify a concurrency level to run tasks in parallel so you don’t need to wait forever for the results.

Statistical rigor (The science part)#

These are the statistical tests currently built-in to the framework:

- Welch’s t-test: For continuous metrics like duration, token usage, or the number of lint issues. We use Welch’s instead of a standard t-test because it doesn’t assume equal variance between groups — which is essential when comparing models that might have wildly different performance profiles.

- Fisher’s Exact Test: For success rates. When you’re working with smaller sample sizes (like 10 or 20 repetitions), standard Chi-squared tests can be inaccurate. Fisher’s gives us a reliable p-value to determine if an 80% success rate is truly better than a 60% one, or just a lucky streak.

- Mann-Whitney U Test: This is our non-parametric workhorse. We use it to compare the distribution of tool calls between successful and failed runs. Because tool call counts aren’t normally distributed (lots of zeros!), Mann-Whitney helps us identify if a specific tool is being used significantly more in the “winning” runs.

- Spearman’s Rho (Correlation): We use this to identify “Determinants of Success.” By calculating the correlation between specific tool calls and metrics like duration or tokens, Tenkai can tell you if a new MCP tool is a Success Driver or just a cost-inflating distraction.

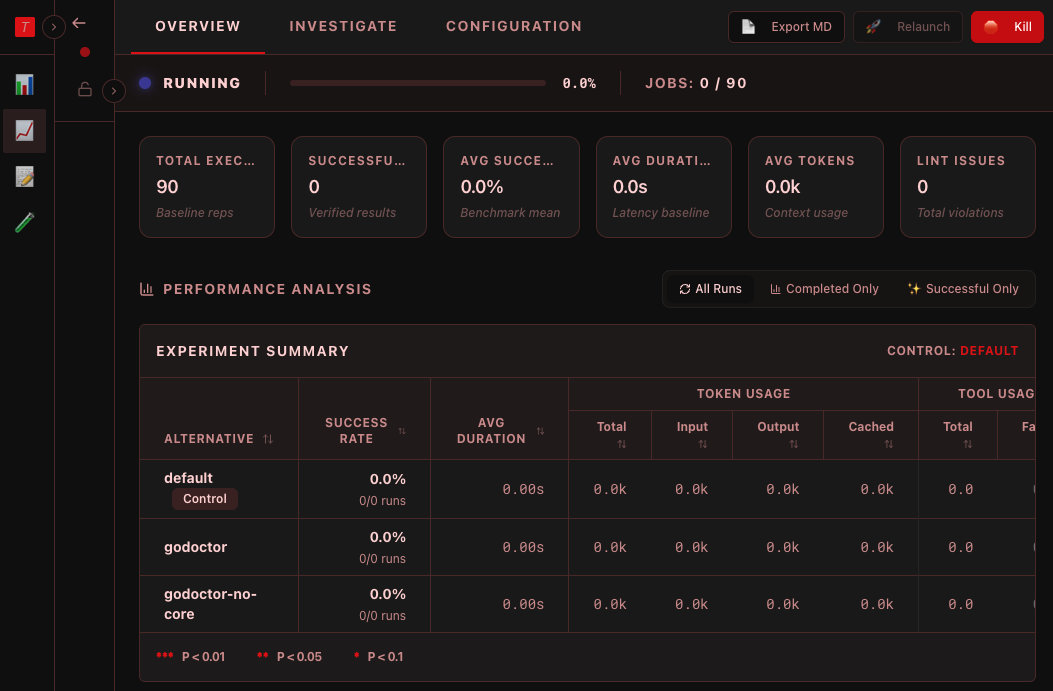

Real-time insights and the dashboard#

As an experiment runs, you can watch the agent’s thought process, see which tools it’s calling, and spot where it gets stuck. It’s like being able to “look inside the mind” of your agent across dozens of concurrent runs.

One of the most powerful features of the dashboard is the ability to filter the analysis on the fly using three distinct “lenses”:

- All Runs: The raw truth. Includes every catastrophic timeout and system error. This is your primary measure of overall system reliability.

- Completed Only: Filters for runs that reached a terminal state (Success or Validation Failure). This is where you go to analyse quality metrics like lint issues or execution time, removing the noise of external timeouts.

- Successful Only: The “Gold Standard” view. By looking only at the winners, you can start to infer why they succeeded. This is where we calculate the Spearman’s Rho and the Mann-Whitney U p-values to identify which tools are highly correlated with success.

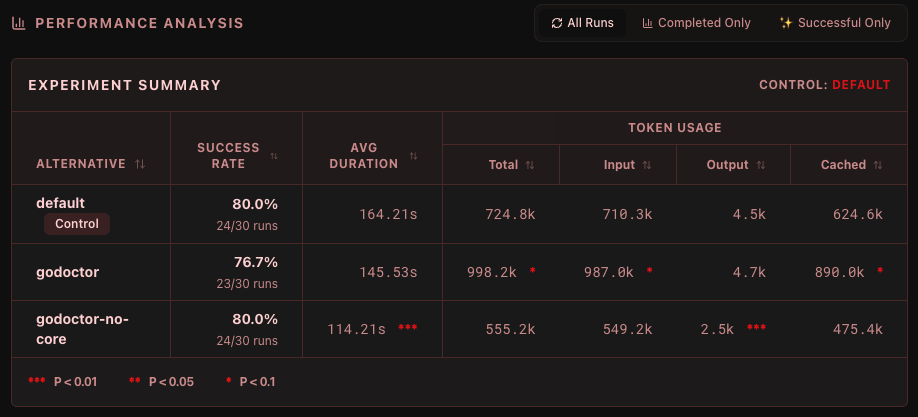

Early results from my own experiments#

I’ve been using Tenkai to refine godoctor into my dream Go-dedicated MCP server. My hypothesis is that by giving the models specialised tools they will become more effective at performing coding tasks. For example, instead of giving the models freedom to decide when to read the documentation to discover the API for a client library, I’m forcing the documentation onto them by returning it every time the model calls go get. This has massively prevented API hallucinations and “dependency hell loops” where the model keeps battling go get and go mod because I thinks it got the wrong version of the package.

Early results also show that this difference diminishes if I pin the model version to the latest generation - Gemini CLI by default launches in “auto” mode, which means it decides automatically which model to call between Gemini 2.5 and Gemini 3, both Flash and Pro versions. By pinning the version to Gemini 3 Pro (model id gemini-3-pro-preview) it becomes much smarter and often procures the documentation by itself (by launching go doc in the command line) in those conflict scenarios, making the godoctor set of tools less impactful.

I also have had many challenges with tool adoption. The models by default have a strong preference to use the built-in tools they have been trained with. Even if I provide a “smarter” tool, they struggle leaving their comfort zone. I failed a lot trying to design experiments around this until I realised my experimentation process was completely flawed. Tool adoption and tool efficacy are orthogonal concepts: by trying to test them both on the same experiment I was failing to produce valid results, so I ended up pivoting to testing only tool efficacy by blocking the model’s access to the built-in tools. This way I finally starting to get better signals about how good (or bad) are the godoctor tools.

If you are curious about how godoctor is shaping to be, and how I came up with the current API, I am speaking about it at FOSDEM next February 1st. Of course, if you can’t attend don’t worry. I’ll also write more about it over the next few weeks.

Conclusions#

We are at a tipping point in software development. We are moving from a world where we write every line of code to one where we orchestrate intelligence.

But orchestration requires measurement. We can’t improve what we can’t measure. The transition from being a writer of code to an orchestrator of intelligence doesn’t mean we do less work — it means we do different work. Our primary responsibility is no longer just the syntax; it’s the Context, the Tools, and the Guardrails.

If we don’t measure the impact of our changes with rigor, we aren’t engineering; we’re just gambling. By moving towards an evidence-based approach to coding agents, we can finally build systems that aren’t just “cool” when they work, but dependable enough to build a business on.

If you’re interested in checking out the code or running your own experiments, you can find the project here

Happy experimenting! o/

Dani =^.^=